योगसंन्यस्तकर्माणं ज्ञानसंछिन्नसंशयम्।

आत्मवन्तं न कर्माणि निबध्नन्ति धनञ्जय।।4.41।।

yoga-sannyasta-karmāṇaṁ jñāna-sañchhinna-sanśhayam

ātmavantaṁ na karmāṇi nibadhnanti dhanañjaya

Actions do not bind the one, who has renounced actions through Yoga, whose doubts have been fully dispelled by Realization and who is poised in the Self, O Dhananjaya

~ Chapter 4, Verse 41

✥ ✥ ✥

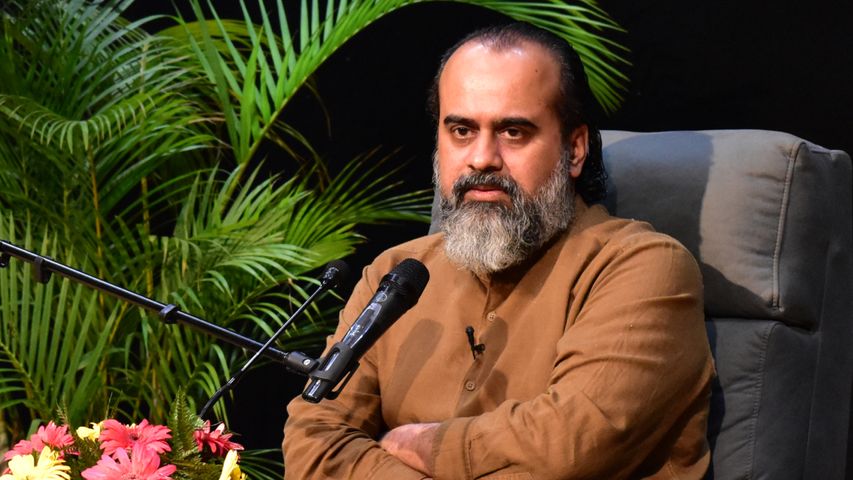

Acharya Prashant (AP): “Actions do not bind the one,” obviously Krishna sees our actions as bondage; that is why he refers to the Yogi as someone whose actions do not bind him. What is this bondage of actions? Let’s go into it, because if we can understand this, then we will know what Yoga is and who that Yogi is who is not held captive by actions.

Actions bind us in two ways which are interrelated, and which are actually one, but for the sake of clarity, we’ll call them two.

Firstly, our actions are not free actions right at the time of their inception. If I push a particular switch and due to that the fan has no option but to act, then surely the movement, the action of the fan cannot be called as free action. The beginning itself is automatic, programmed, designed. And whatever is programmed, externally designed, can also always be controlled by the external. The fan has no right over who would come to push the switch. Anybody can just switch it on, and anybody can come and switch it off. The fan is helpless. The fan would have to act according to the external master’s wishes.

You take two chemicals and drain them together, and what you see is vigorous activity. Do the chemicals have an option there? No, the chemicals are a slave of their properties, a slave of their physical constitution. Action happens without the consent of the actor. The actor has no real say or freedom or independence. The actor is helpless. The actor is designed to act in particular ways in particular situations, and the actor cannot change that.

You boil water to a hundred degrees centigrade, and water has no choice, under normal conditions of pressure, but to evaporate. Water cannot say that “today is a special day, so I won’t evaporate”. Water cannot say that “I am being boiled for irreligious reasons, so I refuse to turn into vapor”. You very well know what you can do to water. The action of the water molecule in turning from the liquid to the gaseous state is predetermined. And anybody who can know this programming of the water molecule can and will control the water. The water will exist just as a hostage of external situations, and all situations are external. Time, place, coincidence, the world, others—these will decide what happens to water.

Same is the case with most of us. We claim that we are acting. But if we are acting, then we must also have an option to not act. When hunger arises, to what extent do we have an option to not eat? The extent to which one can exercise that is probably a determinant of one’s freedom. One belongs to a particular religion and hears a thing or two about that religion. A particular reaction arises from within. It is pre-scripted as to what that reaction would be. If you want to make somebody angry, then you know what to say to him. In fact, others also know what to say to you. They know that your behavior can be controlled through particular types of stimuli.

The biggest proof of that is advertising. Every advertiser knows how to control the behavior of the public at large. Had we really been free beings, how could have advertising succeeded? But advertising succeeds because the actor himself is designed by certain patterns, and those patterns are very common and very easily discoverable; all you have to do is observe.

Observe how people behave and you will know their triggers. Observe how people behave and you will know their keys. Observe how a man behaves and you will know how to decode him. Observe how a woman behaves and you will know how to please her, and therefore control her.

Politicians know that; they know what kinds of promises to make. The priest also knows that; he knows what to offer you, couched in the language of enlightenment of freedom, for emancipation. And because the priest, the advertiser, the politician, the market are not outside of us, it means that all of us in some way know that we are slaves to our own programming, our own designed tendencies. And it’s a very curious thing, a very funny thing. We know that, and yet we are very helpless about it. Someone with the best of intentions will enter your bad books if he behaves in a rough way, and someone whom you know to be crooked would escape with no penalty if he behaves in a pleasant way.

Such is our bondage. In spite of knowing that we are being cheated, we slip. We allow ourselves to be cheated. That is just because chemicals have no control over their reactions, over their responses. The man looks at the woman, and then it’s a matter of the bodily juices, the secretions, the hormones. How would you bring understanding and intelligence to a chemical? You cannot do that. The mother hears the voice of the baby, the kid, and a particular reaction arises almost involuntarily. It is a matter of bodily programming. How would you teach a hormone to be wise, to not be affected by situations?

Hormones can’t turn into a buddha. All that one has been taught and tutored is dead material, and dead material cannot become organic intelligence. So, if one is operating as a fan, if one is operating as a machine or as a computer, then one might be very efficient; one might be very productive—but one is nevertheless still a slave. One might have risen from the status of the primitive abacus to the status of the most advanced supercomputer, but even the most advanced supercomputer is still a slave. The supercomputer is never going to determine what its life is for. The supercomputer is never going to know what Krishna means by Yoga. No machine is ever going to enquire into its own existence. But yes, the machine, by virtue of doing more and more in the dimension of the machine, may gain respectability with other machines because the respectability too is a pattern. We have been taught what to respect and we have no option there.

This is the bondage of actions at the level of the actor. The actor is false. The actor is not the independent ‘I’. The actor is an entity that is a product of circumstances and genes. That which sits as the actor at the center of our ego self is nothing but the one who has as his substratum the physical body that came from the mother’s womb, and then all the experiences that he has accumulated over his lifetime. You can call that his hardwiring and his soft-wiring. You can call that as his hard programming, the operating system itself. And then, the various other programs and applications that sit over the operating system.

What is born from the mother’s body is already programmed and conditioned, and then he keeps on gathering more and more of influences, experiences and conditioning as he moves through time. That is what we are. That is what that actor is. Krishna is saying, “As long as you are that actor, please forget Yoga. Yoga is not for you.” Yoga is freedom from the false actor.

The second kind of bondage with respect to action is the bondage, that attachment to the result of action. The first bondage was the beginning of action. The second bondage is that which we call as the end of action, the result of action. This actor that we take ourselves to be hardly ever acts without an eye on the result. It is not possible for us to ‘just’ act. We act so that we get something. This actor is always hungry; he acts so that he may get something to eat. This actor is always unfulfilled; he acts for the sake of fulfillment. This actor is always a little hollow; he acts to plug in his hollow. This actor is always uncertain and insecure; he acts in order to gain security. So, he’s always wedded to the fruit of his action.

In fact, the more false the actor is, the more certain it is that he would always be looking at the future, always be looking at the fruit of the action. These two things are interrelated. That is why I had said that the bondage of action is twofold, but actually those two folds are just one. Because one begins from the wrong place, hence one ends in the wrong place. And because these two are related, so you need not worry about where you are going to end and what you are going to end up with. You just need to see how you began.

Most of us keep wondering about what the results of our actions would be. You need not wonder. Just honestly look at where the action came from. The beginning of the action is also the end of the action. The first step is the last step. If you can see from where your action is arising, then you have also seen what the fruit of that action is. The fruit of the action is immediate, so you don’t have to wait for two years; you don’t have to wait for the tree to mature and the fruit to appear. If you act from a point of fear, then it is guaranteed that your action will result in more fear. If you act from a point of incompleteness, then it is certain that your action will lead to even more incompleteness. You need not speculate. You need not be hopeful. You need not wish that something against this law may happen because it is not going to happen.

The beginning of the action and the end of the action are one. The source of the action and the fruit of the action are one. This law cannot be violated. We often talk of karmaphala (fruit of action) and that appears quite attractive and mysterious to the ego because karmaphala takes the mind to the future. The ego loves the future. But instead of talking so much about karmaphala, we should rather talk about the Kartā, the actor. The nature of karmaphala is no different from the nature of the Kartā, and the Kartā is who you are. Whatever is your mental state at the time of the action is also going to be the state of the fruit of the action.

This takes away our hopes because we act from a point of fear hoping that the action would take away the fear. Why else does one act? We act from a point of hunger hoping that the action will reduce the hunger. What else is a hungry man going to do? He says, “I’m hungry, so I’m acting so that my hunger may be taken care of.” This hope is always falsified. This wish is always denied. In the apparent world it may so happen that if you are hungry, then your motivation is to get food, and your motivation is fulfilled. So, you start from hunger and end in fulfillment. In the material world it is possible.

In the inner world, in the mental world it does not happen. In the inner world the point that you start from is the point that you end with. So, if you are hungry and you say that “I’m going to a particular person so that he may fulfill my hunger,” then you will find that that relationship leaves you even more hungry. If you start from hunger, then you will end up even more hungry, which means that the only way to gain fulfillment is to be fulfilled right now, is to start as fulfilled. You start as unfulfilled, you remain perpetually unfulfilled.

All methods, all tricks and techniques, all Sadhana (devotional practice), all Tapasya (austerities) are therefore going to fail because the one who enters the techniques—be it Yoga, be it Mantra (verses), be it Tantra (esoteric practice or religious ritualism), be it any other kind of method—he enters assuming that he needs the methods, thereby assuming that he is incomplete. If your basic assumption about yourself is that you are in need of something, that you are incomplete, and because of that assumption you proceed with the action, then that action is only going to give to you more of what you already are—and that is quite incomplete. Hence, all methods are doomed to fail.

You may not have something and you go to a shop and get it, and that makes you feel that the same principle will apply to the inner real life also. It does not happen that way. You keep on feeling an inexplicable insecurity and you feel that the next job would reduce that insecurity, or the next boyfriend or girlfriend would reduce that insecurity, or a new house would reduce that insecurity. That is not going to happen. If insecurity makes you buy a house, that house then stands on and for insecurity; that house pushes you into even deeper insecurity. You may take it for granted that living in that house, you will then be compelled to seek a cure for your insecurity in even bigger ways. You will say, “The house does not suffice now. I need something else to cure my insecurity!”

Krishna is saying, “The Yogi is the one who has realized that Yoga cannot be attained through any method.” Krishna is saying that “the Yogi is the one who has realized that Yoga is one’s nature and trying to practice Yoga is very foolhardy.” Krishna is saying that “the Yogi is the one who does not live in the wish of the future.” Krishna is saying that “the Yogi is the one who has known that Yoga cannot be defined, is not a thing, is not a skill”. Krishna is saying, “The Yogi is the one who is healthy and alright with himself.”

This sentence needs to be heard with caution. When it is said that the Yogi is the one who is alright with himself, it is implied that the Yogi, first of all, realizes who he is. The Yogi is alright seated at the center of his being. His identification with the periphery is just coincidental. For the sake of behavioral convenience he may say that he is an Indian or an Italian, but he does not identify with that. You know an identity? ‘Identity’ means a total unity. ‘Identity’ means A and B are one, which means you could call B as A and A as B and you would be right. The Yogi, just for reasons of convenience, may say that he’s an Indian, but there would always be something extra in him beyond Indian-ness.

So, there is no identity. He identifies only with his empty and full center. He is alright there. He’s seated there. Things keep on happening on the periphery; he places no hopes upon those things. He does not think that whatever is happening at the periphery would enhance him even by one percent, or diminish him even by a centimeter. Not even the smallest increment in his self-worth, in his self-assessment can be brought about by any event that ever happens to him. There are only two abstractions that are impervious to any change. One is an absolute zero, and the other is absolute infinity.

Those who have understood have described the insides of the Yogi, the center of the Yogi using both and neither of these metaphors. Sometimes they have said that he is as empty as the vast sky, and sometimes they have said that he’s as full as the endless ocean. Both are one. You cannot add anything to the sky, and you cannot drain out the oceans. That is who the Yogi is. The Yogi does not wander from place to place hoping to gain enlightenment. The Yogi does not read scripture after scripture. The Yogi does not change job after job. The Yogi does not get into one relationship after the other hoping for something.

Of course, he relates to the entire world—he is totally open and permeable—but he does not relate in order to get a fruit from the relationship. His relationships are instantaneous and fruitless for him. What would an already filled up person want for dinner? What medicine can you give to a healthy man? What riches would attract the one who is already absolutely rich? What can you take away from someone who has nothing? These are all pointers. These point to who the Yogi is.

On one hand, he is the topmost beggar, someone whose net worth is unshakably zero, someone whose trousers have such a large and a gaping hole that whatever you put there is lost. You can never give him even a rupee because whatever you give him is lost from his pocket. His pocket is full of holes—very, very large holes—so his worth remains always zero. Such is the description of the Yogi. He never has anything.

On the other hand, the other description is that of a billionaire. So much he has that in spite of whatever you can take away, he always retains what he has.

Classically, the Shanti Path (peace prayer) of the Upanishads describe the Yogi beautifully. They say that when you take away the Total from the Total, what you have is still the Total. Even if you take away everything that the Yogi stands for, he is still left with everything, which means that he can now be absolutely fearless. He lives in total security. Even if you take away all his possessions, even if you take away all his being, he still remains what he is. Now, who can control such a man? Who can ever dominate such a man? Is the Yogi even a man or a woman?

We must listen to Krishna with utmost sincerity. If we can open up to what he is telling us in these verses, then we would be able to avoid a million traps that lay ready for us. The world is always prepared to lure us into traps. The world is always saying, “Enter my shop, I will improve you! Come to me, I will give you something!” Krishna is saying, “You are the one who cannot be given anything.” The moment you enter a shop, you have reduced yourself. The moment you become hopeful, you have gone away from yourself. Krishna is saying, “Whosoever comes to you and says, ‘Son, there is something wrong with you! I am your well-wisher, I want to help you!’ is your enemy because before he says that he wants to help you, he must say that there is something wrong with you.” Whosoever promises betterment and improvement does you no good. He is giving you a false sense of the self.

To put it more directly, anybody who promises you anything has already betrayed you because all promises are about something that attracts you. Otherwise, it is not a promise at all. Krishna is saying, “To be promised is to be compromised.” Do we see this? Do we see that what he’s talking of is something very-very practical and extremely day-to-day?

The discourse of the Gita was not in some isolated sanctuary or a mountain peak or a yoga center. The discourse of the Gita took place upon a battlefield. The weapons were real. The situation was real. Brothers were fighting for a kingdom. Huge armies stood deranged against each other. So, very immediate, heavy and direct was the situation. It was no time for rhetoric. It was no time for hollow principles. Principles wouldn’t have saved Arjuna.

Just a verbalization of theory, just bookish knowledge would have been of no help. Hence, the Gita is an extremely practical document. But you will have to be an Arjuna to earnestly go into it. You will have to have the state of Arjuna when he was listening to Krishna. Listening to Krishna helped Arjuna beyond measure. It can help you too if you are as devoted to Krishna as Arjuna was. At least in this moment, you should be all ears. If you are, then the Gita will open up something for you that otherwise remains hidden in spite of being extremely immediate. Yes?

In the Gita you have a great discourse because, firstly, it is a great dialogue. Arjuna talks to Krishna. If you are to receive the Gita like an Arjuna, then you must talk. Arjuna is not just a passive recipient. He is an active participant.

Questioner (Q): You said that we are hungry and we want to eat and we can eat. As we eat, we can eat much so we choose how to eat.

AP: This is the great fallacy of choice. Our friend is saying, “I might be hungry, but I can choose to eat little or I can choose to eat more; I can choose to eat this, I can choose to eat that.” Do you know that even this choice is determined by something outside of you?

There have been experiments that have told that the choice of music in a restaurant determines the order that the customers are going to place. Now, does the customer know where the order is coming from? He will think, “It is my personal choice.” He does not even know that the restaurant owner, by manipulating the music, can actually dictate the choice that you are going to make in terms of food. You will be smug in your belief “I placed this order” because you won’t even know that the order is not yours.

By looking at your life history, by looking at your genetics, it can even be broadly predicted what kind of woman you are going to like. And when you will fall in so-called love, you will think that it is your personal decision. It is not your personal decision. You are programmed to fall in love with that particular woman, broadly. Every little thing influences your choices. But we keep on thinking that these are our choices.

The shape of this hall, the color that you are wearing and the color that I am wearing, the intensity of the light here, a little noise coming from outside—everything is dictating the content of our consciousness. But it is nice to believe that our choices are our choices. The ego takes pride. And if it is proven that our choices are not at all our choices, then it feels very humiliating. You very well know how your hunger drops when you meet with certain disappointments. Does that not happen?

The day has not gone well; you don’t feel like eating. Now, is your choice of food your choice? Somebody messaged you that you have had a huge loss in business. Somebody messaged you. It’s a situation outside of yourself. You receive that message and your hunger evaporates; now you don’t feel like ordering anything. Is it really a choice or is it a compulsion? Go into it clearly, please. Do you really have a choice? Where is the choice?

The ego likes to believe that there is something called ‘free will’. There is not. There is only a conditioned apparatus that keeps on working based on a thousand inputs and a thousand stimuli. Your knowledge of what governs you is very incomplete, hence there is some allowance to live in the hope, the mirage that it is my own life. It is not our own life.

Okay, let me go into food.

(Addressing someone in the audience) Which country do you come from, sir?

Q: Iran.

AP: Iran. How do you like khichdi (Khicṛī)?

Q: Khichdi?

AP: Khichdi.

Q: Khichdi?

AP: Khichdi. You don’t like khichdi because you come from Iran. Had you come from Northern India you probably would have liked it. Do you see how your choice of food is not your choice? And did you choose that your parents must be situated in Iran? A coincidence that you were born and brought up in Iran, right? You were born and brought up in Iran. That’s a coincidence. And that coincidence has dictated that you will not like Khichdi.

How do you like Dal bhat (rice and lentils)? Oh! Too bad. Too bad. And if you ask me a particular Iranian dish, I would be as flat as you are because I was not born in Iran.

Do you see everything starting from our political choices, economic choices, food choices, life choices, job choices are dictated by our circumstances?

Q: We think that there are choices but during the action, there are no choices. So does the thinking arises from choices?

AP: This thinking that you are talking of—is there choice involved even in thought? Do you have control over your thoughts? Do you decide what to think about?

Q: It is.

AP: Alright, I’m going into the subject of thoughts. Let us see how free our thoughts are. Let us see whether our thoughts are our own, or whether they are decided by external situations.

Have you been to Lakshman Jhula (a bridge in India)? How many of us have been to Lakshman Jhula? You haven’t been to Lakshman Jhula? Lakshman Jhula is a particular bridge, like any other bridge.

Now, there are monkeys on the Lakshman Jhula, monkeys of all shapes and sizes. Some of them have long tails, some of them have short tails. Kindly don’t think about those monkeys. Please don’t think about those monkeys. Don’t think about the monkey that has a large face. Don’t think of the monkey that was hopping from rope to rope, from wire to wire. Don’t think about the monkey that looked at you as if it wanted to attack you. Don’t think about those monkeys, please! Don’t even let the face of the monkey come into your thoughts.

Now do you see how free our thoughts are? Now do you see that all thought is dictated by the outside?

Thought is the content of consciousness, and all consciousness comes from outside. We do not observe that because we live in a stupor-like state. Because we are not vigilant enough, so we don’t even know where our thoughts are coming from. Hence, we live in the illusion of “my thoughts are mine”.

No thought is yours, sir. Thought belongs to nobody. Only you belong to yourself. And the Self is not a thought. I know it hurts, it pinches because we live in the belief that our thoughts are our thoughts, our choices are our choices, our life is our life. Is it really?

Change your experiences—would your thoughts remain the same?

Go through a different life history—would your thoughts remain the same?

Don’t you see that your life history is dictating your thoughts? And you didn’t choose your life history.

Change even one percent of what you have been through—would your thoughts remain the same?

And add just a little to what you have been through—would your thoughts remain the same?

In fact, just one small bit of information can make your thoughts stand upside down. Does it not happen daily? And then, you are saying, “My thoughts are my thoughts.” Are they?

The Yogi is the one who has moved out of the delusion of thought. He does not identify with thought anymore because he has realized that thought is not who he is. I know this is scary because so much of our investments are based on thoughts. We thought out our next wife; we think out our next move. Everything that we do is a thought out decision. And if thought does not belong to us, then it proves that all our decisions are just hollow. We do not like to hear that—but please hear that. Better late than never.

If you read a little bit of what is going on in the field of experimental consciousness, then you would realize that it is possible to change your thoughts by connecting two electrodes to your brain. Some trained researcher can give whatever thoughts that he wants to give you under controlled conditions of experiment. You tell what you want to think, and he’ll make you think that way. And you tell what you do not want to think, he’ll make you think that way. And you don’t need to do so much. An extremely attractive woman passes by in front of you—can you resist thinking about her? Don’t you see that the thought is not yours? The thought is situational. She came and the thought came—is the thought yours? Had it been yours, how could it have arisen with the arrival of the woman? How?

One shot of some chemical and you will start thinking things that you don’t normally think of. One little surgery and so many thoughts will be wiped out of your mind. Are your thoughts yours?

But we live in thoughts. We are deeply identified with thoughts, so this statement does not appear sweet. We have invested heavily in thoughts, and no one wants to hear that his investment has been in the wrong thing.

The Yogi is the one who is the master of his thoughts―in the sense that he does not live by his thoughts; his thoughts live by him. Thoughts do not touch him; his being guides his thoughts―rather he lets the thoughts be.